Account of my correspondence with the English serial killer Ian Stewart Brady.

(In my book – in French only – “The Words of Evil – My Correspondence with Killers,” you will have the opportunity to discover more in a much more developed form, rich in twists and additional anecdotes.)

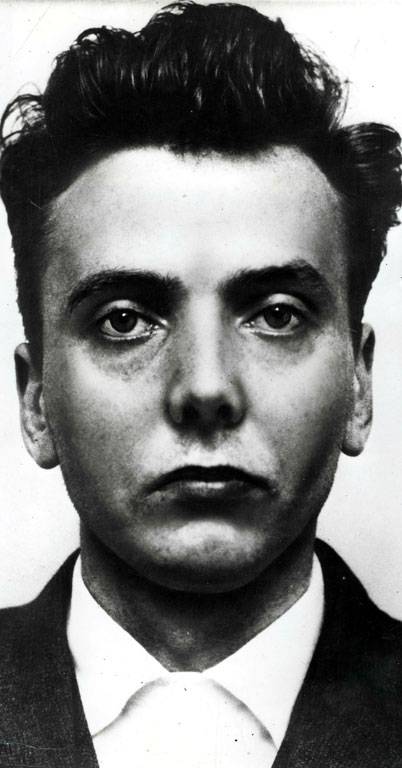

The case of the Moors Murderers has always intrigued me for its magnitude and the indelible imprint it left on consciousness. How could two seemingly ordinary office workers commit such terrible acts before being arrested, traumatizing England for several generations? Corresponding with a pedophile and psychopathic serial killer is not an easy thing. It’s difficult not to pass judgment and maintain perspective, but I wanted to form my own opinion on the personality of Ian Stewart Brady. However, it was impossible for me to communicate with his partner, Myra Hindley, who died in 2002.

I began writing to Ian Stewart Brady in 2010. Detained in the Ashworth high-security hospital, I was apprehensive that my correspondence would be immediately prohibited, but that was not the case. More than a month after my first letter, on April 22, I finally received a response from the Moors Murderer. His cramped and trembling handwriting suggested to me that he was under neuroleptics. Ian Stewart Brady had a distinctive writing style. His sentences were convoluted but indicated a certain intellectual refinement. His reflections reached a high level of analysis and philosophical maturity.

According to him, it was important to handle words skillfully and have a rich language, two fundamental elements for the benefit of elaborate thinking. In his very first letter, he expressed his satisfaction that my keen interest had been sparked by his book titled “The Gates of Janus.” He explained that his work is now allowed in British and American universities. Ian Brady’s book is very interesting, but it’s important to keep in mind that he consciously or unconsciously (probably a bit of both) tries to intellectualize his criminal acts to find legitimacy through his in-depth analyses of psychology and the world of men.

He admits this himself regarding his murders: “It was an existential exercise.” For example, he often employs the theory of moral relativism, fully aware of the concepts of good and evil. In this way, “The Gates of Janus” is indeed the book of a psychopath, cold and calculating. More than the substance of his thoughts, it’s the use he makes of them that reveals much about him. Since his youth, Brady loved Dostoevsky, especially “Crime and Punishment,” which was his favorite book. He strongly identified with its main character, the young murderer Raskolnikov, who, in a situation of great poverty, constantly questions the legitimacy of his actions through the following question: “Is murder morally tolerable if it leads to an improvement in human condition?” In the last years of his life, he recommended that I read “Language and Silence” by Georges Steiner when we were corresponding. This book dissects the power of language, its meaning and consequences, as well as its fragility and the threats it faces, such as its instrumentalization and manipulation.

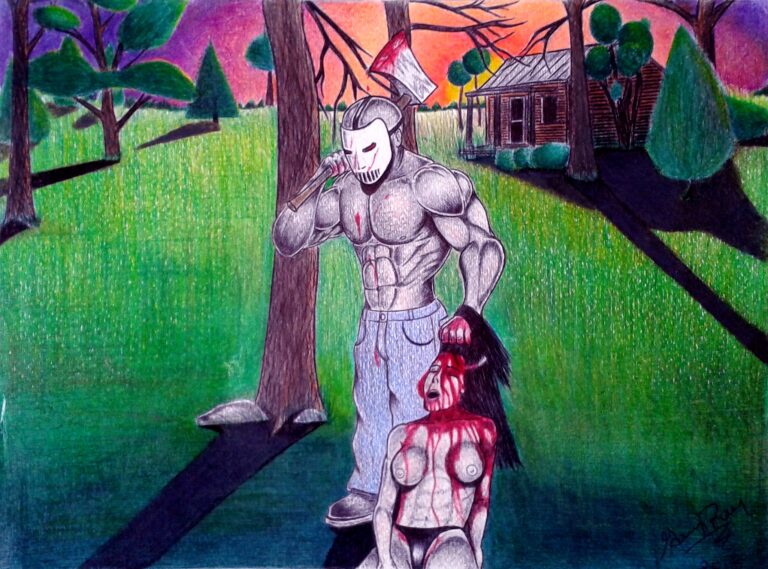

Once again, the theme is relativism. In a way, Brady spent his life dissecting his own propensity for crime and his psyche, both to understand himself and to navigate the paths of crime, using all possible arguments to give meaning to his choices. Ian Stewart Brady’s book provides a very personal approach to serial murder through a narrative divided into two distinct parts. The first part discusses his view of society, his conception of good and evil, the concept of moral relativism, and he demystifies the serial killer. The second part is dedicated to the systematic study of famous serial killers such as Ted Bundy or Richard Ramirez. Informed of my interest in painting and art, Ian Stewart Brady told me that one day he had created two surrealist studies that had earned him an award at the “Koestler Awards Exhibition.” (“The Koestler Awards Exhibition” is an exhibition featuring works created by inmates. It is organized by “Insider Art” at the Institute of Contemporary Arts in London.)

“Yes, I tried oil painting in the 70s. I created two surrealist studies for which I received an award at the ‘Koestler Awards Exhibition.’ I never repeated the experience. I tried here, but they discourage any form of positive creativity because it highlights the negativity of the administration and these parasites that are the personnel [prison staff] here.”

I quickly felt the shadow of Dostoevsky hovering over Ian Stewart Brady’s letters, as many were the quotes and references from the Russian author. He also often expressed his opinions on international politics. It was a recurring theme in his letters. Sometimes, he briefly reminisced about his life as a free man, recounting several times his motorcycle or steam train travels in Belgium and France, aiming to acquire firearms or pursue other criminal interests. His love for France was palpable, and he often praised the delights of our regions.

“Yes, I have traveled to France several times to buy weapons in Belgium, before managing to ensure an unlimited supply in the UK. I always stopped in Paris, even if it was sometimes just for one night. When I traveled by car, I preferred to take the country roads and taste the wines and cheeses of small villages, where old stone buildings and cobbled alleys were rocked by history. I also visited Germany, Austria, and other places in the East – the Eastern villages, plunged into darkness, seemed to belong to a completely different era, but not the 20th century; the darkness retained only the musty smell emanating from the foliage and the plowed and damp earth.”

Filled with resentment and resignation about his own condition, he briefly described his daily life at Ashworth Hospital and often referred to the healthcare staff as “baboons.” One day, he informed me that he was claiming his right to die and had been on a hunger strike since 1999, while being force-fed through the nose with a tube by the staff at Ashworth Hospital. Interned for nearly 40 years in a cell at Ashworth Hospital, Ian Stewart Brady felt no remorse for his crimes. Worse, he constantly intellectualized his deeds to better justify them and give them meaning. In a letter dated April 26, 2012, he sent me a recorded audio cassette. It was a personal compilation containing numerous excerpts and music from films in various genres. All these chosen pieces were not accidental and spoke volumes about his view of life.

Ian Brady finally died on May 15, 2017, from cancer, at the age of seventy-nine, taking some of his secrets to the grave. Until the end, he cast doubt on the location of the remains of one of his victims, who was never found. From the depths of his cell, he psychologically tortured the mother of little Keith Bennett, whose body is still somewhere, probably on Saddleworth Moor. Thus, Ian Brady ultimately had the last word. The most hated man in England, he was undoubtedly the worst serial killer of the twentieth century in all of Britain, and his case left an indelible mark on the collective unconscious, akin to Jack the Ripper in the 19th century.

“Even serial killers are not quite what they seem. They can sometimes be the rope stretched over the spiritual abyss, between man and his disappointed hopes.”

Ian Brady, The Gates of Janus, 2001.