Born in 1980, holder of a master’s degree in Literature and a DUT (University Technology Diploma), Etienne Ruhaud is the Parisian author of “Petites fables” (Rafael de Surtis editions, 2009), “La poésie contemporaine en bibliothèque” (L’Harmattan, 2012), and a social novel “Disparaître” (Unicité editions, 2013). He directs the literary blog Page Paysage. He also participates in public readings of texts. Etienne Ruhaud chose to grant me an interview about my interest in drawing and painting. I gladly accepted his interview proposal, which differs from others usually focused on my activities around serial killers.

Etienne Ruhaud: When and how did you start painting or drawing? Did you receive any formal training?

David Brocourt: I started when I could hold a pencil between my fingers, around four years old. At the very beginning, I drew naive things like ducks or Santa Clauses. Quickly, still in a childish manner, I moved on to fantastical creatures, monsters, and quite detailed war scenes with soldiers shooting at each other or bombings on inhabited buildings. Perhaps I was unconsciously influenced by the evening news? It’s probable. In the 80s, televised media had fewer filters than nowadays and regularly reported on the war in Lebanon. The presenter often advised parents to keep their children away from the TV to avoid them seeing blood, corpses, or fights, for example.

My fondness for mutant and monstrous creatures probably stems from the fact that my father had some magazines on fantastic cinema. He hid them high up on a shelf, and I wasn’t allowed to touch them. Of course, this prohibition only magnetically attracted me to those publications.

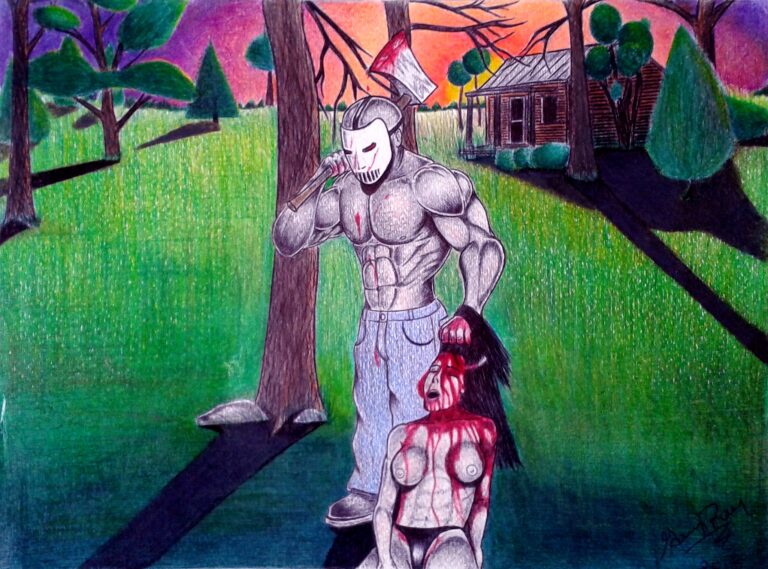

So, by the age of eight or nine, I discovered characters like Chucky, Freddy Krueger, and many others. They terrified me but fascinated me at the same time. In parallel, with my parents, I became acquainted with films more suitable for my young age, such as The NeverEnding Story, The Goonies, Willow, Beetlejuice, Star Wars, and E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial. I was fond of fantasy and science fiction films. Later, around the age of ten, I crossed a threshold by discovering Robocop, Terminator, Predator, and Alien. I was drawing monsters or robots all the time back then! I also sculpted them in modeling clay.

In adolescence, I eagerly immersed myself in horror productions such as the sublime Dellamorte Dellamore, Brain Dead, Candyman, Hellraiser, Cabal (Nightbreed), and many others. Some of these films derive from the literary work of Clive Barker, an extremely prolific author, director, screenwriter, and painter. Regarding the Alien film series, it was only a bit later that I learned the creator of the monster was none other than the Swiss painter and sculptor, H.R Giger. The universe he created, with dark and symbolic eroticism, completely fascinated me, and it still does today. Beyond the morbid aspect, I perceived all the poetry and romanticism that permeated horror films.

Their numerous social parables and philosophical inquiries into the human condition prompted deep reflections in me. The subversive films of directors David Cronenberg, David Lynch, and John Carpenter put many of my existential questions into perspective. They made me feel good and provided answers about myself at a time when I sought to understand who I was and what I was doing in this world.

I was heavily influenced by comics, especially DC or Marvel comics, not to mention artists like Enki Bilal, Moebius, and Juan Guiménez. I drew techniques, a sense of proportions, etc., from them. As you may have understood, I am 100% self-taught. When I wanted to make drawing a serious activity around the age of 20, all doors closed in front of me. In fact, I can even say they never opened!

The schools, all private, were too expensive, and the Fine Arts were inaccessible because I had messed up my entire schooling. But even if it had been different, this direction would have been denied to me by my parents who considered this path completely sterile in terms of professional prospects. Anyway, at that time, my priority was to support myself due to an unfavorable family situation. I was frustrated and bitter, living my passion for drawing and painting more or less like a failure or a lonely loser’s passion.

E.R.: Many of your paintings are in black and white. What is your relationship with color and line?

D.B.: I don’t use color primarily because the relationship between shadow and light fascinates me completely, as well as all the shades of gray that can be obtained by playing with black and white. What also interests me is the placement of emptiness in my works. A set of lines drawn on a sheet composes the drawn subject and distributes the space around it. This space also expresses something.

This notion is found in Japanese prints. In Japanese culture, emptiness and spaces are a whole concept. That of “MA” (間) which means “interval,” “duration,” “space,” “distance.”

This concept does not respond to geometric considerations but to an intuition linked to aesthetics and continuity. MA is the interval between the lines that separates and connects them. In Japanese calligraphy, the essence of the thing is in the line itself, and it is never abruptly interrupted because that would “kill” the sequence and the living intervals that make the life of the line. The line is then considered dead.

By observing Japanese calligraphy, you can see that the characters do not form distinct lines but, on the contrary, a coherent whole. That’s why a character is never interrupted or resumed in the middle of the road. With MA, the idea is to create a living whole.

MA is therefore not a search for emptiness, and it is not the exploration of nothingness. On the contrary, it is the overcoming of the duality of emptiness and fullness. The use of so-called “empty” spaces only serves to give it meaning. In Japanese culture, emptiness is not synonymous with nothingness, unlike what is thought in the West. It is part of fullness, and one cannot exist without the other. It is a natural balance and a cosmic principle.

E.R.: What techniques do you use?

D.B.: Fairly basic techniques. I draw with India ink using a good old drawing pen, as classic as it gets, and I paint with acrylic or ink using brushes that are all over twenty years old. I take great care of my equipment, cleaning it after each use, and manage to keep it in more than decent condition.

Regarding ink drawing, I always start with a preparatory pencil sketch. That’s the first step. The more precise the sketch, the more I will know where to go during the inking or painting fill. Of course, I have to be careful not to kill the spontaneity of the pencil sketch line. The final result depends on it. I sometimes literally ruin the life force of a drawing with improper use of ink or paint.

In drawing, the concept of MA makes sense in sketches that are not necessarily perceived as unfinished but, on the contrary, constitute a set of open lines full of liveliness revealing the aesthetics of improvisation. Purists do not know erasers, and the line must be pure, perfect at the first stroke.

India ink allows you to work on this. There is no room for error! A smudge during the inking of the pencil sketch, and the whole drawing is thrown in the trash. It’s frustrating when that happens. But sometimes, the accident actually adds an aesthetic touch. What’s interesting about the accident is to try to control it to integrate it into your technique to provide beautiful effects.

E.R.: You wrote a book about your relationship with serial killers, “Les mots du mal – Mes correspondances avec des tueurs” published by Camion noir editions in 2018. You also collect murderabilia, works of ”art” produced by murderers, sometimes very famous. To what extent do serial killers inspire you?

D.B.: What intrigues me about works produced by serial killers or other categories of incarcerated criminals is the authenticity that emanates from them. Often produced in the discomfort of a prison cell and created with limited means, they tell something. I find anthropological and sometimes artistic interest in them. The works produced by criminals often reveal a lot about their psyche. If some are simple reproductions, others are genuine projections of their fantasies and aspirations. Sometimes, they are reminiscences of their crimes that provide insights into their modus operandi or their preferences in terms of victims. In any case, the works of criminals are valuable documents to help understand them.

E.R. : As an author, do you think that other forms of creation nourish your work? Does literature, music, or cinema have an impact on your activity as a visual artist?

D.B. : When I am in the creative process, I am completely absorbed in what I am doing for several hours. I can draw and paint while listening to music or with the television on, playing a movie of my choice. What I listen to doesn’t influence the subject itself but more the rhythm at which I will produce it. Dark, joyful, slow, fast, organic, or electronic music will have a different effect on my state of nervousness and the tension of the strokes. But I don’t really pay attention to all of this in the moment. Sometimes, silence is good too. I am then much more attentive and receptive to my own internal music, such as my breathing or the tension I feel in my muscles. The exercise then becomes a kind of meditation or gymnastics.

In a more general sense, it seems to me that evolving comfortably for years in a dark cultural universe influences the tone of my productions. Other artists have had a major influence on me. The paintings of Francis Bacon and Vladimir Velickovic, the drawings of Egon Schiele, as well as the photographs of Joel-Peter Witkin and David Nebreda, deeply moved me when I discovered them.

You will have understood, I am impregnated with all sorts of things. I spend time reading books and watching films. It’s a need. More specifically, the literary work of H.P Lovecraft captivates me to the highest degree, and I sometimes feel like I share, on my own scale, many of his existential anxieties. This author had the genius to conceive a complex and intense work, difficult to render in images as its strength is expressed primarily in the mind.

E.R. : Can you tell us about your influences? Do you feel close to any particular painter?

D.B. : The painted bodies by the artist Vladimir Velickovic have always impressed me greatly. A little over ten years ago, I saw an exhibition of his works in an art center, at the Temple de Chauray (79). I arrived at the opening at 1 p.m. and didn’t leave until 6 p.m., kindly pushed towards the exit by the person managing the place. This exhibition was a huge shock for me. Before that, I had only seen one of his works in real life, at the Fine Arts Museum in Pau. It was a body of a dead man, gray and headless, resting on an autopsy table with the identification label attached to his big toe. In addition to painting, Vladimir Velickovic produced an countless number of ink drawings. His stroke is sharp, nervous, and of absolutely staggering surgical precision! His entire work expresses the struggle for life.

Also, the rigorously and compulsively drawn sketches by the Austrian painter Egon Schiele had a strong impact on me. This artist drew with a pencil, never used an eraser, and did not hesitate to go over his sketches in different places to emphasize, in the way he desired, the curve of a hip or the shape of a calf. His drawings are a true frenetic and erotic exploration of the human anatomy. Obsessive and as tyrannical with himself as with his models, he constantly sought to capture the human body from all angles to reveal all its subtleties in the most raw and authentic way possible.

E.R. : Your works generally depict creatures, anthropomorphic chimeras in a state of suffering. Do you have models, or does it all come from your imagination? Where do you draw this strange inspiration?

D.B. : I don’t know if my creatures are really in a state of suffering. Some of them smile and seem to play with their condition. They are born as they are, so what the viewer may perceive as a painful state is simply the normal state of the creature since its conception. My monsters have nothing to regret or even hope for. They just are.

Regarding inspiration, I have no other models than those that come to mind. Often, I am in front of my blank sheet or canvas without knowing exactly what I am going to do. In the absence of a specific idea, it’s more of an emotion or energy that passes through me. Sometimes, I do have a theme in mind, but I can completely deviate to do something else. Except when I intend to draw something or someone already existing, I have no idea at all what I’m going to do. The subject comes out like that.

In general, I don’t spend more than a day on a work, but I may not rush to ink it and spend several days on it. Hurrying is not good and can lead to irreparable mistakes. It’s important to take your time.

To guide me, when I create complex views of the body from specific angles, I use my own body and, from time to time, photos of anatomical models. For example, for hands, which are perhaps the most difficult part of the human body to reproduce, I use photo models when I don’t contort mine at the desired angle, to the point of sometimes getting cramps.

From time to time, I draw directly from references I love, such as horror cinema or fantasy literature. It’s quite exclusive, and it’s more for the sake of the exercise. Recently, I paid a modest tribute to Lovecraft in an ink drawing depicting an inhabitant of Innsmouth undergoing a transformation. The short story titled “The Shadow over Innsmouth” is the first Lovecraft story I read. I was about fifteen years old. It was a shock that reconciled me with reading. At that time, I was rather resistant because I was being forced to read about topics that didn’t interest me, and I was being asked to renounce the comics that I loved. But for the first time, I was completely absorbed by this Lovecraftian story.

It tells the story of a young man who is an enthusiast of ancient civilizations and desires to learn more about the origins of New England. He discovers Innsmouth, a stinking and filthy coastal village with strange inhabitants. The young man observes strange physical anomalies in them. As he investigates, he discovers that the villagers worship an impious deity from the depths of the ocean or even from another dimension, and that they are all mutating to be able to join their ideal in the depths of the sea to live eternally, in wonder and glory.

Another time, I had fun creating Elmer, the brain twister, the atypical creature from the 80s horror film of the same name, which is a parable about drug addiction. Elmer is a large, centuries-old worm that needs a host to live. In order to be tolerated by the person he decides to occupy, he injects a euphoric and ultra-addictive drug into the back of their neck, opening up a range of heightened perceptions but generating a rapid and painful addiction when the withdrawal sensation occurs. Since its appearance in the Middle Ages, Elmer has passed from hand to hand or rather from neck to neck throughout history, driving everyone who became addicted to its hallucinogenic nectar completely insane. Elmer speaks, and he is a philosopher. Over the centuries, he has had plenty of time to learn about human functioning to better exploit its weaknesses and exhaust its resources. This film is as funny as it is disturbing.

E.R. : What is your relationship with dreams and nightmares? Can we talk about oneirism?

D.B. : I attach great importance to my dreams or nightmares. I often remember them and meticulously record those that strike me the most in notebooks. Some of my creations are directly inspired by them.

I don’t know if we can talk about oneirism in my works, but what is certain is that I attach great importance to the power of imagination. I like to think that dreams and nightmares are projections of our inner universes, moments belonging to another dimension, perhaps as true and powerful as reality itself.

I like to think that true reality is denatured, truncated by all our sensory perceptions. Indeed, it is scientifically accepted that our relationship with reality and how it is apprehended differs greatly among individuals. The world of the psyche (unconscious) may be more authentic, more complete, and less subject to the dictatorship of our senses, or even our ego, which sometimes misleads us about the interpretation we make of the world around us and of which we are a part.

E.R. : Your work remains quite dark, marked by death, anxiety. Is art, for you, an outlet? Can it make you happy?

D.B. : Indeed, I am naturally anxious. Art is for me not only an outlet that allows me to vent my anxieties but also a tool to try to understand the emotional and materialize it, to offer a different perspective on the world. In a way, it is a way to make them solid to better expel them. It is a means of making something abstract, aesthetic, or beautiful, communicating it to the world so that it exists in the eyes of others, and they can share their impressions.

This allows me to approach my works in a different way, taking into account the opinions of those who contemplate them and give me feedback. It is often pointed out to me that there is something Lovecraftian in my creations. For me, this is the most honorable compliment one can give me. However, I have no intention of depicting Lovecraft’s universe but rather my own.

I will always find it interesting for two distinct people to feel and perceive the same object in a totally individual way (although there are similarities in the analysis). Different points of view enrich it and give it multiple meanings. It is through this multiplicity of perspectives that we access higher levels of reflection and understanding. I think that in this sense, art helps to understand oneself and the universe around us, to achieve a certain intellectual and spiritual fulfillment. It is a means, among others, to become an actor in one’s life and to strive for a certain harmony.